by Carol S. Hyman

‘Tis the season when the mind turns to giving. But how many gifts through the years are keepers? How many do we even remember? Diamonds may be forever but most stuff tends to go the way of all things.

So what do we keep? Memories, of course, but science indicates that every time we recall a memory, it changes slightly, aligning more with the story we hold about it. Pictures of an event may even replace memory, standing in, a token of the time.

After forty holiday seasons with my husband, this is the fourth without him. Thinking back on the gifts he gave me, I realize most have gone on into other hands in the downsizing since his death. More and more I’m coming to realize that the greatest gifts he gave me in sharing his life so generously weren’t material goods anyway.

In the early years of our marriage, our disagreements focused largely on what music to listen to. His opinion was that, with a few exceptions, notably jazz, what had been written in the last seventy-five years was hardly worth listening to and certainly not more than once. I, on the other hand, loved popular radio. If I couldn’t sing along with it, I wasn’t much interested.

The lead-up to the epiphany that changed that dynamic is too long to tell here; the short version is that with gentle persistence he fostered my desire to share his joy. I eventually surrendered to a love affair with the old music he loved so much. Bach. Verdi. Puccini. Brahms. And Beethoven, the star of this story, albeit with a more contemporary supporting cast.

Even being almost totally deaf did not stop Beethoven from persisting in bringing the sounds that arose in his mind out into the world. Innovative sounds. Sometimes almost otherworldly sounds. Including what might arguably be called one of the greatest gifts anyone has ever offered humanity, the finale of his Ninth Symphony, the “Ode to Joy.”

Beethoven conducted its first performance, although there was another conductor, one who could hear and who requested that the orchestra and chorus follow his lead rather than the composer’s. When the piece ended, Beethoven remained facing the musicians, with his back to the audience and not until one of the soloists, a favorite of his whom he had enlisted for the contralto part, walked over and turned him around did he discover how profoundly his music had stirred the crowd, all jubilant and on their feet.

So it is with the greatest of gifts: they bring us together. They lift us out of our little cocoons and invite us to share time with one another.

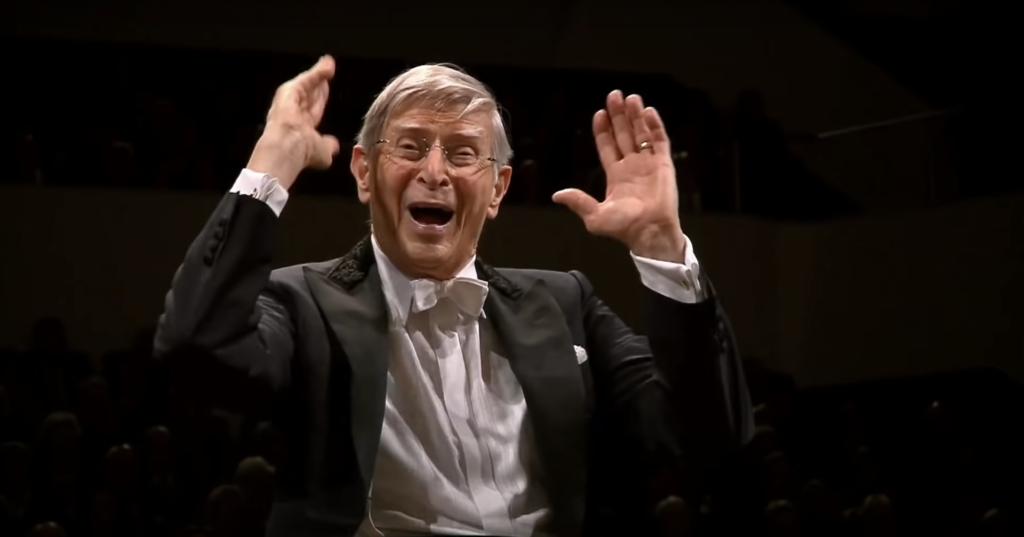

This holiday season I have been sharing time with a seventeen minute YouTube video. Contemplating the dedication it took – all those musicians mastering their instruments and their voices and laboring in rehearsal to bring them all together – is inspiring and slightly daunting. And the joy the conductor manifests and the range of emotion on his face as the glorious sounds dissolve into silence never fail to move me to tears.

Truth told, the tears often start soon after the first notes sound. No wonder the EU chose this as their anthem. It inspires gratitude to be part of the human stream that celebrates our goodness. And Maestro Blomstedt, now well into his nineties, proves that it’s never too late to share that.

You can watch it here. If you can, listen with headphones and watch on a big screen and definitely keep your eye on the conductor, all the way until the screen turns black. Then if, like me, you want to know more about him, read this profile in the New Yorker.

Since I don’t pay for commercial-free YouTube, each time I listen, the performance is interrupted for a few seconds about half-way through. Somebody is trying to sell me something. It might even be the perfect gift. But I skip the ads, confident that I’m tuning in to a greater treasure, a gift worth keeping. The “Ode to Joy” is only one of many. Keep your eyes peeled and your ears alert for what brings us together. Then spend your time and attention on those. That’s the best gift you can possibly give.