Minding Our Inner Weather

by Carol S. Hyman

In brainstorming, people spontaneously offer ideas without considering whether they have merit or not. “Don’t edit yet” is the basic principle; gather what arises in the collective mental space and sort out what has value later on. The term also aptly describes the way thoughts and emotions spontaneously arise in our minds, an inner brainstorm in which, unless we apply mindfulness, the second part of the technique, sorting out what’s valuable, can tend to get lost.

If you’re in the public eye, others will notice your brainstorms. “His life was a kaleidoscope of constantly shifting moods,” was written about an American president, but this one was articulate and introspective enough himself to admit there had been “very many times in my life when I have been so agitated in my own mind as to have no consideration at all of the light in which my words, actions, and even writings would be considered by others.”

Let’s hear it for self-awareness. It takes a certain amount of it to recognize, even after the fact, that one has a tendency to spread one’s storms around. But to notice an impending squall in time to self-correct, or at least consider the trajectory and potential consequences of what we’re about to unleash, calls for more than that.

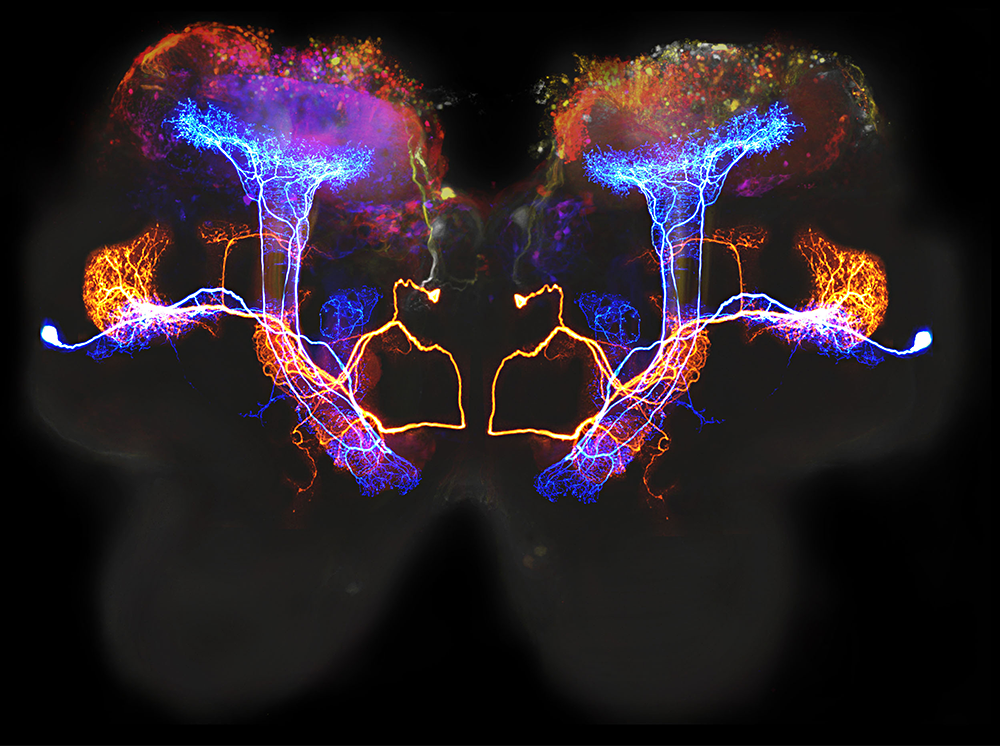

We need to be able to direct our attention to our emotional state, detect our inner weather patterns, and discern the most skillful and productive way to respond to our circumstances. That’s hard to do in the heat of the moment, which is why training the mind is such a good idea. Once we get used to paying attention to our inner state as well as to what’s around us, we start seeing patterns in how the two interact.

Here’s an example: yesterday I was feeling productive and full of energy for tackling the day’s tasks, which included projects that called for creativity as well as a number of conversations. One of those, early in the day, turned slightly contentious—not exactly an argument, but edgy. I briefly interrupted it to take a call from my daughter, whom I very much wanted to talk with; I promised to call her back shortly and returned to the meeting. When it was over, I noticed that I felt a little less enthusiasm for the day, as if edginess lingered in the atmosphere, clouding my vision of what to do next.

I returned my daughter’s call, only to discover that she’d had a minor accident and wasn’t really in the mood to talk any more. Hanging up, I could feel the cloud of edginess deepening into what felt like a fog of futility. The day’s remaining tasks no longer interested me. I had thoughts of reaching back out to one of the people I’d recently talked with to try to fix my discomfort, but experience has taught me that in-house repair is more productive.

Had I found myself in that mood in a formal office environment, I’d probably get busy with something relatively rote, like clearing out my inbox or filing things. But since I work from home and can set my own schedule, and since it was a sunny spring day, I decided to take a short walk. Things are just beginning to bud and bloom here in northern Vermont, and as I walked, I watched my attention toggling back and forth between the beauty of the world around me and a nagging sense of unease within me.

That’s how it is to be human. We simultaneously inhabit multiple energetic spectrums. In any moment, we may find ourselves anywhere along any of them, from impulsiveness to inertia, from stability to transition, from being inspired to being depressed, from feeling empowered to feeling like a victim. If we recognize and gain familiarity with our energetic patterns, we can learn to see what triggers reactivity and so avoid jumping the gun.

One of our favorite ways of jumping the gun is to beat ourselves up over where we happen to be, inner weather-wise. I noticed that tendency on my walk: an inner voice telling me that I shouldn’t let things affect me so much, that I should just get over it and tune back into the gusto I had felt earlier. That is what one wise teacher called “negative negativity”: when we’re not only having a hard time but are making it worse with our strong desire not to be experiencing what we do. Recognizing that process, I practiced staying present, watching awareness move back and forth among burgeoning fiddlehead ferns, birds busy building nests, blue skies, and my lingering sense of unrest, which seemed to change slightly each time I tuned into it.

I wouldn’t mind being able to say that, as if by magic, when I got back I felt refreshed and ready to dive into the next project. But that wouldn’t be true; I started to work and then realized I didn’t feel I could muster the necessary creativity for it. Instead, I took care of some domestic tasks and mulled over what I might learn from the day’s experiences.

After a good night’s sleep, I woke ready to tackle that item from yesterday’s to-do list: to finish writing this blog post, of which I had done only one paragraph. And as I pondered what direction to go, I felt gratitude for the training in applying mindfulness I’ve had that let me ride out yesterday’s weather without allowing my mood to wreak damage in the world around me.

Constantly shifting and kaleidoscopic is actually how life is for all of us, and our moods are part of that. Even for those of us who aren’t president, consideration for the light in which others might see our behavior is a quality worth cultivating. And for those worried about brainstorms in the White House, take heart: the country survived the president referenced earlier—John Adams!